Yom Kippur is long.

25 hours filled with prayer and introspection. 25 hours filled with a lot of sitting and standing in synagogue.

25 hours filled with not eating or drinking, not wearing leather shoes, not wearing perfume.

From sundown to sundown Jews have this one day a year, this day of atonement. According to what I have been taught (15 years of Hebrew Day School ahoy!), God has a book of life, and in it, he inscribes your fate for the year to come on Rosh Hashanah, our new year, and he seals the deal and closes the book ten days later on Yom Kippur. So, this day of atonement is a sort of last chance to change God’s mind, to ask forgiveness. We spend the day in synagogue, striking our chests and confessing to all of our wrongdoings. We spend the day fasting. I assume these two things are both for the same reason, to make us suffer, in body and in mind.

This year, I tried to make it a meaningful day. I tried to use this day as an opportunity to think about this past year—about who I am and about who I want to be next year. As I sat inside the stuffy synagogue, I was feeling NOTHING other than horrible coffee withdrawal. Standing, sitting, listening, saying the words. It was all meaningless to me. Just as I was about to break out into my best version of Nothing from A Chorus Line, I accidentally flipped to one of the last pages of the Yom Kippur prayer book. And I discovered a section that I had never seen before. Likely, I’m sure, because this particular section begins on page 849, and by, oh, about the 560s, I’m over the service completely.

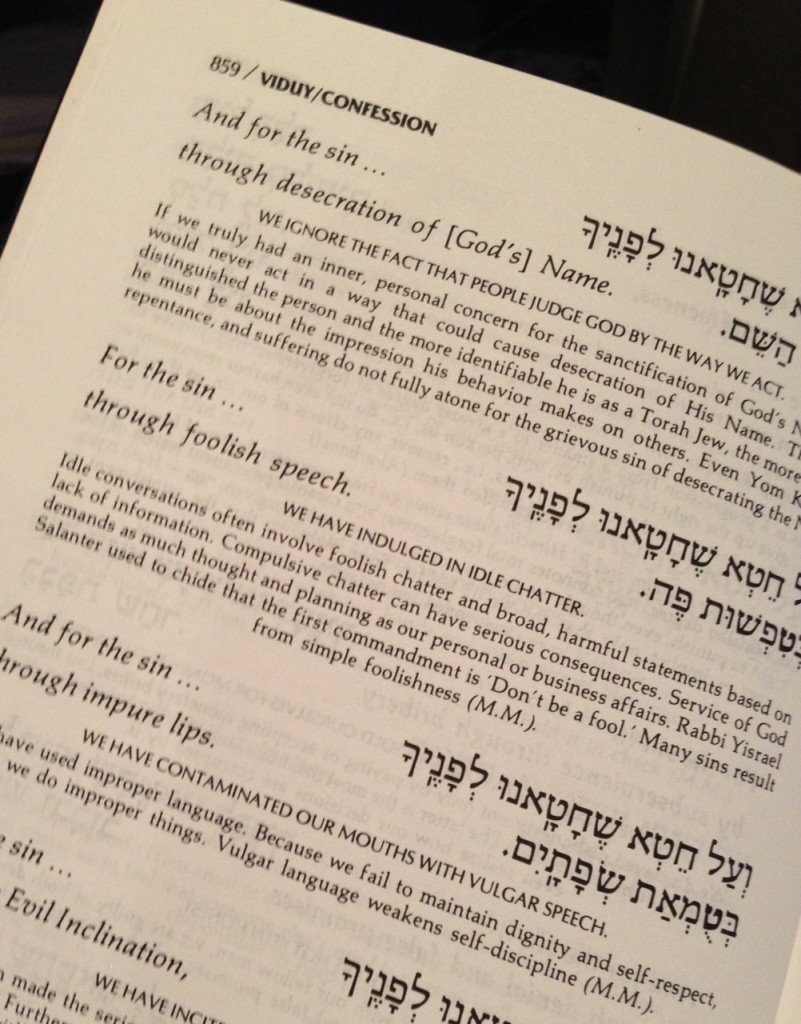

You see, a big portion of the day’s service includes something called Vidui, which translates to confession. Each man, woman, child, recites these many transgressions, and strikes him or herself on the chest while saying each Hebrew word, describing a wrongdoing. I have said these words. I have been saying them since I was a child. These words have never meant a single thing to me. Not one thing. It was an action, it was a reflex, it was just something you did in synagogue on Yom Kippur.

This back section that I found, the one that begins on page 849, breaks each sin down. It not only translates each one, but it explains, in detail, what each one means.

So, my daughter Emily and I sat in the very last row of the synagogue, and we read each one together.

For the sin through hardness of the heart.

That one, even translated into English, doesn’t really mean much to me. Hardened heart? WHA? So, the back of the book tells me this, by way of an explanation: We have refused to admit we might be wrong. We have had the attitude of ‘I am always right!’

Both Emily and I looked at each other, smiled, and realized that we have both done this. We have also done some of the other ones—spoken too harshly, have been too quick to say yes, have not always respected our parents.

So, while the rest of the synagogue stood and sat, spoke and listened, struck themselves on their chests and recited transgressions, Emily and I sat at the back of that room and whispered to each other. We talked about things we have done this year, things we have done ever. We talked about the ones we feel badly about, and the ones that even though they are written in this book, we don’t really think are wrong, at least not for us.

This, actually, was the most meaningful Yom Kippur I have ever had. Possibly the only meaningful one I have ever had. And it had absolutely not a single thing to do with the prayer book. It had not a single thing to do with fasting. This idea of suffering—of sitting all say uncomfortably in prayer, of spending all day depriving our bodies of nutrients—seems a bit ridiculous, a lot ridiculous. For me, it was sitting with my daughter, chatting in hushed tones about being a better daughter, a better friend, a better person.

But you know, I could have had a much better conversation with her had we been sitting in our living room, had I been drinking a hot cup of joe. I would have been REALLY able to think about who I was this year and who I hope to be had I not been depriving my body of basic necessities.

And you can sign, seal, and deliver that into my book of life.

16